Boomtown: city-making in the west

Nearly a decade on from the opening of Elizabeth Quay, how has Perth’s city centre evolved and where to next for WA’s booming capital?

In this piece we speak with Andrew Lilleyman, Director and lead of ARM’s Perth studio, and Caroline Hickey, Principal, to reflect on Perth’s transformation during a time of sustained economic growth and cultural momentum. From the landmark RAC Arena – part of the city-shaping Perth City Link strategy – to the state’s first vertical primary school on the CBD’s eastern edge (with EIW), ARM has been a quiet force in shaping the urban form and civic identity of contemporary Perth.

As the city expands, densifies and diversifies, Andrew and Caroline share their insights on Perth’s future, its design opportunities, and the role architects can play in making a booming city more liveable, connected and enduring.

It’s been nearly a decade since Elizabeth Quay opened. In your view, how has Perth’s city centre changed since then – physically, culturally, and in terms of how people experience it?

Andrew Lilleyman: Currently at Elizabeth Quay (EQ), the building sites are almost all complete – two of the original 10 sites are yet to be delivered. These things take time. At the very start of the project, we had always viewed it as a 15 to 20-year project, from public realm delivery to a fully operational precinct with active sites around. Now we are seeing other projects developing around the city, ECU on the William St spine, Concert Hall, and the proposed Aboriginal Cultural Centre.

With EQ, we are starting to see how it works as an entire precinct, with active promenades, restaurants and retail, public transport, and kids’ spaces – people are using it as intended!

Elizabeth Quay, designed by ARM with TCL and Richard Weller, 2024. Photo: Jenny Watson.

Beyond the Esplanade, the Quay has brought the much-needed ‘Y-axis’ into focus, adding another dimension to how people move across the city from north to south. Historically, Riverside Drive, St George’s Tce, Hay and Murray Streets moved people through and would even bypass the city along dominant commercial and retail corridors. I think EQ and other new projects along William St create a cultural spine – EQ, ECU/Yagan Square, the Cultural Centre, and the Museum.

Caroline Hickey: I think there is a good reason to walk down to the waterfront – something to go to. It’s hard to remember what was there before, but it was a large square of green lawn and road –yes, the river is beautiful and impressive, but there was not much to attract people down to the river from the city. There were always those north-south links through the city, but now they’re moving people differently. And whilst we talk about the town’s inhabitants, such as workers, locals, etc. EQ is an identifiable area to visit in Perth. So, for tourists, it’s a place to add a day to the itinerary before heading to the regions.

RAC Arena, by ARM and Cameron Chisholm Nicol. Photo G Hocking.

ARM has contributed to some of Perth’s major city-shaping projects – including EQ, RAC Arena, and now the East Perth Primary School – each playing a role in transforming key parts of the CBD. What urban challenges were these projects responding to, and how do you reflect on their impact today?

CH: We like these kinds of projects. They are pretty challenging and place a lot of pressure on good communication.

AL: There are many hurdles to overcome, and there are many people in the conversation with masterplans, so the strategy needs to be well-conceived and able to adapt when required. Projects like EQ owe a lot to the big thinkers, and when I think of EQ, I think of our time working with Richard Weller. He pitched projects high, made them compelling, and had no time for negative thinking. He was great to work with.

For my part, and Julian Bolleter’s, it was making sure the material (the design work) was as evocative as the thinking, so we would go into design presentations with big ideas and ambitious imagery. So much conceptual work was done, so many options were tested.

CH: I often find this aspect overlooked because when something works, it simply works, but it often takes a lot of exploration to get there. There is a consistent method in the ARM office, depth of research, thinking, and testing options. It’s not a whim or a repeat of the last project. It’s responsive. We listen and try to respond to all of the competing demands.

AL: We aren’t importing ideas into the area; we are constantly wondering what will make these places unique to Perth and WA and developing principles from scratch. There is deep diving research from all aspects – cultural and urban connections. There are always challenges, and we are deploying an approach (a strategy) that can take the many slings and arrows.

Concept render for East Perth Primary School, by EIW x ARM, the first vertical primary school in WA, currently in design.

CH: RAC Arena, EQ and East Perth Primary School are all very different typologies with differing site concerns. I think what has been consistent with all of them has been an attempt to maximise the opportunity they present. We have gone into those projects with eyes wide open, and certainly not with a scheme in hand. If we are too presumptuous with projects, we can be quickly proven wrong. Or there is often a history to projects that we need to unravel. The waterfront has 50 years of attempts at schemes, so understanding why they haven’t worked, or what they did achieve, is in part a way to move forward on the project. It is also a lot about timing – being the right time, the right people, the momentum to move something forward, so it’s not just about the architecture. There is a risk that projects don’t happen. They lose that momentum, political support or a myriad of other risks to dodge. We keep them all in mind!

WA is in a period of growth and prosperity – but what does that mean for the future shape of the city? What opportunities and risks do you see as Perth expands and densifies?

CH: I often ponder how WA’s economy rides its own wave. It’s a big state. It has big resources and a very broad range of social, cultural and environmental issues that are specific to here. In saying that, we do architecture, which can enhance or contribute to all of these things, but ultimately, our contribution is the infrastructure.

There is a lot of space to work on in Perth, which is an exciting prospect. We are about to get a new university building in the city, a new inner city primary school, and an Aboriginal Cultural Centre. These are key moments for change.

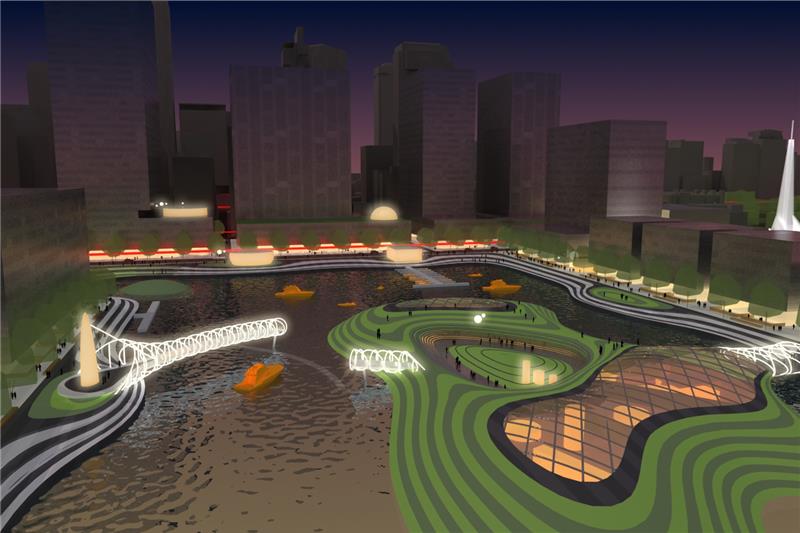

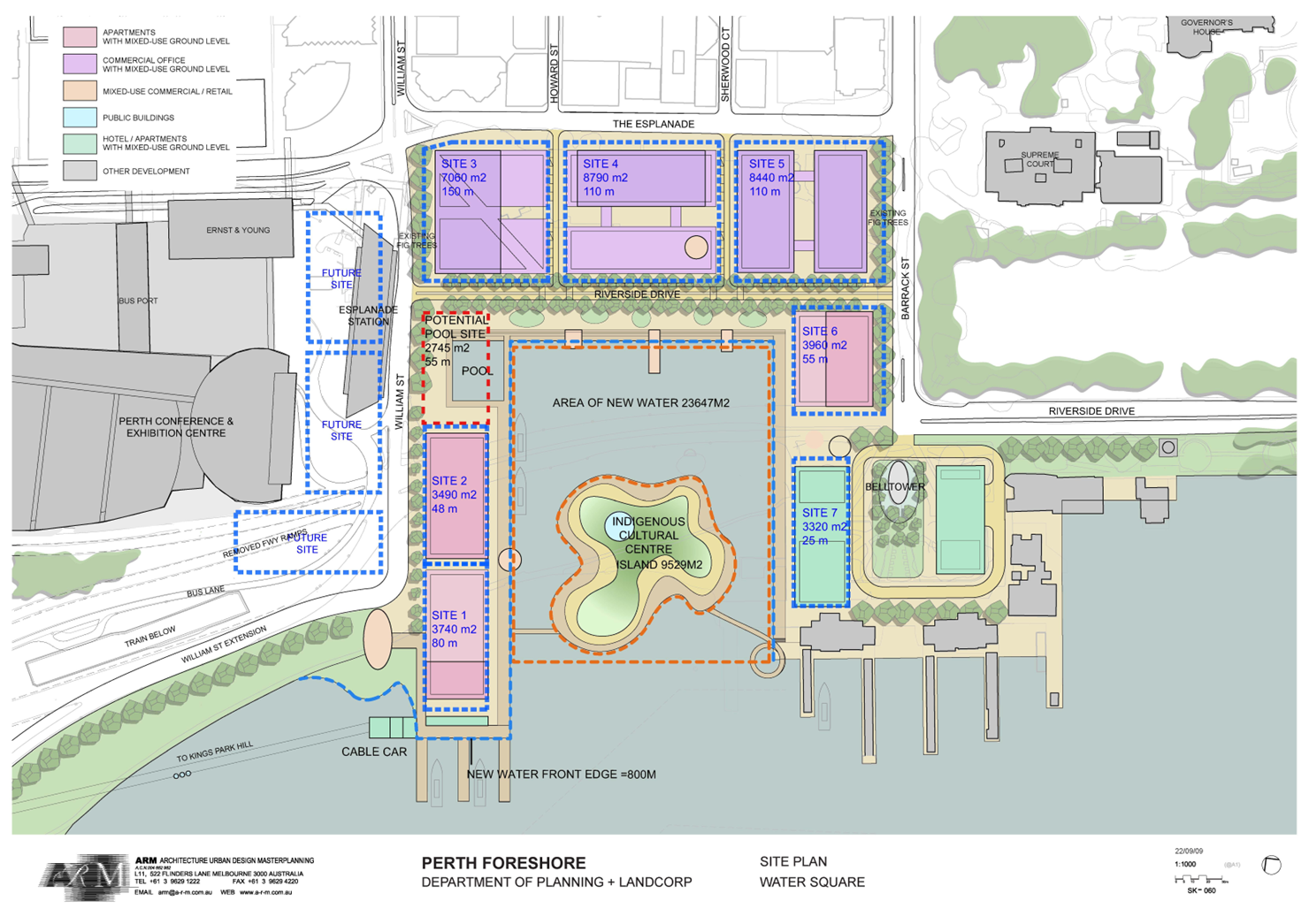

An early concept design iteration of Elizabeth Quay, featuring an ‘inverted island’ housing an Aboriginal Cultural Centre.

AL: We first contemplated the idea of an Aboriginal Cultural Centre in Perth when it was originally part of the waterfront masterplan. We had looked at a few versions. When we switched to a Liberal Government, the ACC was incorporated into that project as a cultural counterpoint to the creation of development sites – sort of soft form versus hard commercial architecture. From memory it was an idea borne from discussions between Richard Weller and Howard Raggatt and gained momentum in the working groups.

The scheme had various iterations. Its initial concept was as a negative island in the middle of the precinct, something that exposed and therefore allowed you to connect with the base of the river, as though you were moving back in time. It was too radical. It later became the whole island, and then later again, it found its way to the bottom of William Street as a site out in the water.

CH: In its current brief, the ACC is still part of the waterfront precinct, now positioned on the other side of the Supreme Court gardens. So, we are beginning to see cultural sites along the water’s edge.

AL: These projects are very much about future gazing – what is the next 20, 50, 100 years look like in the city. As architects we try to capture the spirit and ambition of the moment, building in the now. We think architecture is a built record of what our beliefs or values, and what is important to us – to design is to say something about these beliefs.

CH: The new East Perth Primary School is a major step for city. As is the new ECU campus in the city. Traditionally these have been beyond the CBD, along network corridors. So, bringing them back is a larger statement about the city changing and maturing. Not just the place to work and leave to the suburbs after 5pm – but a place live, to dwell, with families. There is opportunity for more of course. A new contemporary art gallery would be good!

An early concept design iteration of Elizabeth Quay, featuring an ‘inverted island’ housing an Aboriginal Cultural Centre.

Compared to eastern capitals, Perth has often followed a different rhythm. Do you think Perth is forging a unique model of city-making, and if so, what does that look like?

AL: I’ve often tried to think about this idea of place. I’m not sure I’ve been able to put my finger on what makes Perth, Perth. But whether you are talking about the local climate or the Perth economy, there is this cycle to Perth of long periods of dry, then downpours. It produces the most resilient of outcomes – a hardened style of work that is durable and often restrained, but then often, a spectacular flourish comes with it.

CH: Historically, the largest and most commercial architecture firms can withstand this environment, and unsurprisingly, the city has an efficient, commercial vernacular, which has been successful and is hard to move past.

AL: But I am really interested in why things are the way they are. Why do most buildings look like commercial undertakings in the city? What does building an apartment tower in a town that has been zoned commercial for decades mean? What does local look like in a state where most building materials are imported? How do you make something enduring, cultural, and commercially successful in Perth? Lots to ponder.

What role should architects and designers play in ensuring Perth’s current period of development has long term benefits for the city?

CH: I think the only role architects can play in ensuring the city’s benefits is to do their job to the best of their abilities. We do not finance projects or build them. Our power lies in listening, investigating, problem-solving, and coordination; the right design/idea can respond to all those things, and when built, those issues become invisible, and that unlocks a different experience, whether that be of a live event, the waterfront, a retail precinct or the experience of having a home for the first time. I think it’s the diversity and quality of experience that is going to ensure Perth is resilient.

AL: I think we work best when the opportunities for change can occur, and or methods or working and integration align with that. We are certainly drawn to projects that have challenging briefs, or difficult sites, or culturally complex, and sometimes all the above.

We like to channel the clients’ ambitions on projects. It is an interesting time to work on the school project, as the government is looking at education briefs for the design of schools. There are opportunities for new design drivers and opportunities to formalise these in a project and demonstrate them as working models, so that they can be benchmarked for future schools.

CH: So, I suppose all of these projects could be considered catalysts for the city now and in the future.

Footnote: Boomtown refers to Richard Weller’s book Boomtown 2050: Scenarios for a Rapidly Growing City, published by UWA Publishing. We’ve titled this interview as a nod to Richard’s significant contribution to imagining Perth’s future and in recognition of our close working relationship with him.